AUTOMATION HISTORY

856

Total Articles Scraped

1474

Total Images Extracted

Scraped Articles

New Automation| Action | Title | URL | Images | Scraped At | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 🤖 Day 42: Embodied AI — Robots with Brains 🦾🌍 | https://medium.com/@samriddhisharma.vis… | 0 | Jan 31, 2026 16:00 | active | |

🤖 Day 42: Embodied AI — Robots with Brains 🦾🌍URL: https://medium.com/@samriddhisharma.vis/day-42-embodied-ai-robots-with-brains-8b534d85cd14 Description: 🤖 Day 42: Embodied AI — Robots with Brains 🦾🌍 What happens when AI leaves the chat window and walks into the world? That’s Embodied AI — where in... Content: |

|||||

| Embracing Embodied AI: Surgical Robotics | https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbest… | 0 | Jan 31, 2026 16:00 | active | |

Embracing Embodied AI: Surgical RoboticsDescription: Coupled with robotics, AI-based simulations can expand access to top-tier surgical training while improving real-world outcomes. Content: |

|||||

| Tesla überfordert: Optimus ist zu komplex - Produktion mehr als … | https://winfuture.de/news,154183.html | 10 | Jan 30, 2026 16:00 | active | |

Tesla überfordert: Optimus ist zu komplex - Produktion mehr als halbiertURL: https://winfuture.de/news,154183.html Description: Tesla muss seine Pläne für die Massenproduktion des Optimus-Roboters drastisch zurückschrauben. Die Produktion wurde zwischenzeitlich sogar komplett ... Content: Images (10):

|

|||||

| Humanoider Roboter Optimus arbeitet nicht produktiv bei Tesla | heise … | https://www.heise.de/news/Humanoider-Ro… | 1 | Jan 30, 2026 16:00 | active | |

Humanoider Roboter Optimus arbeitet nicht produktiv bei Tesla | heise onlineDescription: Elon Musk hat eingestanden, dass der Roboter Optimus noch lerne und wenig produktiv sei. Ein verbesserter Nachfolger soll in Kürze vorgestellt werden. Content:

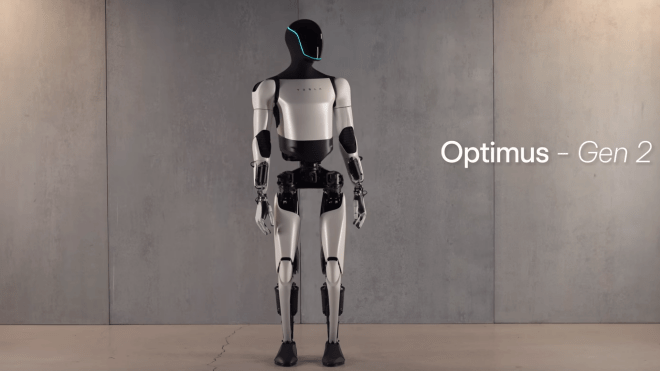

Elon Musk hat eingestanden, dass der Roboter Optimus noch lerne und wenig produktiv sei. Ein verbesserter Nachfolger soll in Kürze vorgestellt werden. Humanoider Roboter Optimus von Tesla (Bild: Tesla) This article is also available in English. It was translated with technical assistance and editorially reviewed before publication. Don’t show this again. Teslas Roboter Optimus ist doch nicht so nützlich, wie bisher immer behauptet. Das hat Tesla-Chef Elon Musk bei der Vorstellung der aktuellen Quartalszahlen zugegeben. Dennoch will Tesla in diesem Jahr die Serienfertigung des humanoiden Roboters starten. Im Sommer 2024 kündigte Musk an, den Roboter ab 2025 in der Produktion einzusetzen. Er hat eingestanden, dass er damit zu voreilig gewesen sei: Statt der Anfang 2025 versprochenen 10.000 Exemplare des Optimus hat Tesla deutlich weniger gebaut. Auch Musks Ankündigung, die Roboter würden nützliche Arbeiten in der Fabrik ausführen, war übertrieben. Der Roboter werde derzeit nur in geringfügigem Maße in den Tesla-Fabriken eingesetzt und lerne noch, sagte Musk in der Telefonkonferenz mit Analysten und Anlegern. Eine große Hilfe für die Arbeiter waren sie dabei aber offensichtlich nicht: „Wir haben Optimus ein paar einfache Aufgaben in der Fabrik erledigen lassen.“ Damit scheint er nicht weiter zu als Mitte 2024: In einem Video, das Musk bei der Jahreshauptversammlung zeigte, war ein Optimus zu sehen, der Akkuzellen in eine Kiste einsortierte. Der Roboter stehe noch am Anfang, gab Musk zu. „Er ist noch in der Forschungs- und Entwicklungsphase.“ Die aktuelle Optimus-Version 2.5, hat Probleme mit den Händen. Im ersten Quartal 2026 soll laut Musk der Nachfolger kommen. Optimus Gen 3 werde „große Upgrades“ bekommen. Dazu gehöre unter anderem eine neue Hand. Mit der Einführung von Gen 3 werde Tesla die älteren Roboter ausmustern. Optimus Gen 3 ist dann auch die Version des humanoiden Roboters, die Tesla in Serie bauen will. Die Serienfertigung soll Ende des Jahres starten. Geplant sei, sagte Musk, eine Million Exemplare im Jahr zu bauen. Videos by heise Die Roboter sollen im Tesla-Stammwerk in Fremont im US-Bundesstaat Kalifornien gebaut werden. Dafür wird im zweiten Quartal 2026 die Produktion des Model S und des Model X beendet. Tesla hat im Jahr 2025 zum ersten Mal seit Jahren einen Umsatzrückgang verzeichnet: Der Gewinn lag um 46 Prozent unter dem des Vorjahres. (wpl) Keine News verpassen! Jeden Morgen der frische Nachrichtenüberblick von heise online Ausführliche Informationen zum Versandverfahren und zu Ihren Widerrufsmöglichkeiten erhalten Sie in unserer Datenschutzerklärung. Immer informiert bleiben: Klicken Sie auf das Plus-Symbol an einem Thema, um diesem zu folgen. Wir zeigen Ihnen alle neuen Inhalte zu Ihren Themen. Mehr erfahren. Nur für kurze Zeit: 7 Monate heise+ für 7 € pro Monat lesen und zusätzlich zu allen Inhalten auf heise online unsere Magazin-Inhalte entdecken.Exklusiv zum 7-jährigen Jubiläum: Lesen Sie 7 Monate heise+ für 7 € pro Monat und entdecken Sie zusätzlich zu allen Inhalten auf heise online unsere Magazin-Inhalte. Nur für kurze Zeit!

Images (1):

|

|||||

| Milagrow Alpha Mini 25, Yanshee and Robo Nano 2.0 humanoid … | https://www.fonearena.com/blog/471206/m… | 1 | Jan 29, 2026 16:00 | active | |

Milagrow Alpha Mini 25, Yanshee and Robo Nano 2.0 humanoid robots launchedContent:

Fone Arena The Mobile Blog Milagrow today launches three new humanoid robots aimed at transforming learning, research, and consumer engagement. The lineup includes Alpha Mini 25, Yanshee, and Robo Nano 2.0, designed to transform how children learn, how students and researchers explore AI and engineering, and how businesses interact with customers. Together, these robots represent a new era of robotics: emotionally aware, highly functional, and designed for education, research, and commercial environments, the company said. Alpha Mini 25 is a compact humanoid robot for children, homes, and classrooms. It is 245mm tall, weighs 700g, and combines education and play to support AI-powered learning, conversation, and creative activities. The robot is portable for use both at school and home. It assists with daily routines, homework, creative play, and emotional support. In classrooms, it enhances learning by demonstrating concepts, supporting reading, math, and early STEM education, and engaging learners with interactive feedback. Key features Quick Specs Yanshee is an open-source humanoid robot designed for schools, universities, research labs, and maker spaces. It has a robust aluminium-alloy frame with 17 precision servos, enabling realistic humanoid motion. Its modular design and layered computing architecture support experiments from basic coding to advanced AI and machine learning. The robot provides a research-grade environment for students and professionals to test theories, prototype models, and apply academic concepts in practical engineering. It enhances hands-on learning in coding, mechanics, control systems, and AI applications. Key features Quick Specs Robo Nano 2.0 is a 19kg humanoid service robot designed for public and commercial spaces such as retail, hotels, hospitals, airports, and educational campuses. It features a 13.3-inch HD display and advanced sensors for autonomous navigation and customer engagement. The robot delivers continuous service including visitor guidance, information provision, and interactive engagement. It helps organizations improve operational efficiency, reduce staff workload, and maintain consistent service quality. Key features Quick Specs Available online at milagrowhumantech.com and offline at Vijay Sales stores in India. All three robots come with a 1-year warranty. Speaking on the launch, Amit Gupta, S.V.P. of Milagrow Humantech, said, Today’s world demands solutions that are intelligent, adaptable, and human-centred. At Milagrow, we believe robotics can redefine how we learn, research, and connect with people. With Alpha Mini 25, Yanshee, and Robo Nano 2.0, we are bringing emotionally aware, interactive, and highly capable humanoid robots into everyday life—supporting children’s learning, empowering students and researchers, and transforming customer interactions. These robots are not just machines; they are companions, collaborators, and problem-solvers. As society becomes increasingly digital, we see these innovations as essential tools for fostering creativity, understanding AI, and enhancing human experiences across homes, classrooms, and public spaces.

Images (1):

|

|||||

| UF researchers deploy robotic rabbits across South Florida to fight … | https://www.yahoo.com/news/uf-researche… | 1 | Jan 29, 2026 16:00 | active | |

UF researchers deploy robotic rabbits across South Florida to fight Burmese python explosionURL: https://www.yahoo.com/news/uf-researchers-deploy-robotic-rabbits-160321123.html Description: Version 2.0 of the study will add bunny scent to the stuffed rabbits if motion and heat aren’t enough to fool the pythons. Content:

Manage your account Scattered in python hot spots among the cypress and sawgrass of South Florida is the state’s newest weapon in its arsenal to battle the invasive serpent, a mechanical lure meant to entice the apex predator to its ultimate demise. Just don’t call it the Energizer bunny. Researchers at the University of Florida have outfitted 40 furry toy rabbits with motors and tiny heaters that work together to mimic the movements and body temperature of a marsh rabbit — a favorite python meal. They spin. They shake. They move randomly, and their creation is based on more than a decade of scientific review that began with a 2012 study that transported rabbits into Everglades National Park to see if, and how quickly, they would become python prey. “The rabbits didn’t fare well,” said Robert McCleery, a UF professor of wildlife ecology and conservation who is leading the robot bunny study that launched this summer. Subsequent studies revealed that pythons are drawn to live rabbits in pens with an average python attraction rate of about one python per week. But having multiple live rabbits in multiple pens spread across a formidable landscape is cumbersome and requires too much manpower to care for them. So, why not robot bunnies? “We want to capture all of the processes that an actual rabbit would give off,” McCleery said. “But I’m an ecologist. I’m not someone who sits around making robots.” Instead, colleague Chris Dutton, also a UF ecology professor but more mechanically adept, pulled the stuffing out of a toy rabbit and replaced it with 30 electronic components that are solar-powered and controlled remotely so that researchers can turn them on and off at specific times. The rabbits were placed in different areas of South Florida in July 2025 for a test phase that includes a camera programmed to recognize python movement and alert researchers when one nears the rabbit pen. One of the biggest challenges was waterproofing the bunnies so that the correct temperature could still be radiated. Python challenge: Why state recommends not eating Florida pythons McCleery was reluctant to give specifics on where the rabbit pens are located. “I don’t want people hunting down my robo-bunnies,” he said. Version 2.0 of the study will add bunny scent to the stuffed rabbits if motion and heat aren’t enough to fool the snakes. State efforts to mitigate python proliferation have included a myriad of efforts with varying degrees of success. Renowned snake hunters from the Irula tribe in India were brought in to hunt and share their skills. There have been tests using near-infrared cameras for python detection, special traps designed, and pythons are tracked by the DNA they shed in water, with radio telemetry, and with dogs. Also, the annual Florida Python Challenge has gained legendary status, attracting hundreds of hunters each year vying for the $10,000 grand prize. This year’s challenge runs July 11 through July 20. As of the first day of the challenge, there were 778 registered participants, from 29 states and Canada. But possibly the highest profile python elimination program is the 100 bounty hunters who work for the South Florida Water Management District and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The hunters have removed an estimated 15,800 snakes since 2019 and were called the “most effective management strategy in the history of the issue” by district invasive animal biologist Mike Kirkland. Kirkland oversees the district’s hunters. He gave a presentation July 7 to the Big Cypress Basin Board with updates on python removal that included McCleery’s robo-bunny experiment, which the district is paying for. “It’s projects like (McCleery’s) that can be used in areas of important ecological significance where we can entice the pythons to come out of their hiding places and come to us,” Kirkland said at the board meeting. “It could be a bit of a game changer.” The Burmese python invasion started with releases — intentional or not — that allowed them to gain a foothold in Everglades National Park by the mid-1980s, according to the 2021 Florida Python Control plan. By 2000, multiple generations of pythons were living in the park, which is noted in a more than 100-page 2023 report that summarized decades of python research. Pythons have migrated north from the park, with some evidence suggesting they may be able to survive as far north as Georgia if temperatures continue to warm and more pythons learn to burrow during cold snaps. More: Snake hunters catch 95% of pythons they see. Help sought to kill the ones that are hiding In Palm Beach County, 69 pythons have been captured since 2006, according to the Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System, or EDDMapS. In addition, four have been found dead, and 24 sightings have been reported. Big Cypress Basin board member Michelle McLeod called McCleery’s project a “genius idea” that eliminates the extra work it would take to manage live rabbits. McCleery said he’s pleased that the water management district and FWC, which has paid for previous studies, are willing to experiment. “Our partners have allowed us to trial these things that may sound a little crazy,” McCleery said. “Working in the Everglades for 10 years, you get tired of documenting the problem. You want to address it.” McCleery said researchers did not name the robot rabbits, although he did bring one home that needed repair. His son named it “Bunbun.” Kimberly Miller is a journalist for The Palm Beach Post, part of the USA Today Network of Florida. She covers real estate, weather, and the environment. Subscribe to The Dirt for a weekly real estate roundup. If you have news tips, please send them to kmiller@pbpost.com. Help support our local journalism, subscribe today. This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Python challenge: Robot bunny new weapon to fight invasive in Florida

Images (1):

|

|||||

| "Inteligentes", adoráveis e arrepiantes: Estes robots não deixam ninguém indiferente … | https://tek.sapo.pt/multimedia/artigos/… | 1 | Jan 29, 2026 16:00 | active | |

"Inteligentes", adoráveis e arrepiantes: Estes robots não deixam ninguém indiferente - Multimédia - Tek NotíciasDescription: O mundo da robótica continua a avançar com inovações concebidas para melhorar o trabalho em ambientes como fábricas e facilitar a vida doméstica. Dos robots com aspecto cada vez mais "humano" aos assistentes para o dia a dia, veja os modelos que se destacaram este ano. Content:

Em 2025, a “corrida” dos robots acelerou, sobretudo no que toca aos modelos humanoides. Ao longo dos últimos meses, várias fabricantes apresentaram as suas propostas, concebidas tanto para serem utilizadas em fábricas como nos lares, com robots de companhia e assistentes domésticos. Da Tesla à Figure AI, passando ainda pela Boston Dynamics, Apptronik, Unitree e LimX Dynamics, múltiplas empresas aproveitaram para demonstrar as proezas dos seus robots, seja a dançar, fazer acrobacias de parkour, a combater nos ringues, a fazer golpes de kung fu ou a arrumar a loiça. Apesar do entusiasmo, surgem novas preocupações, incluindo receios relacionados com a substituição de trabalhadores e perda de postos de trabalho para humanos, ou com uma nova "bolha" no sector dos robots humanoides, com alertas vindos da China. Mas uma coisa é certa: ao longo deste ano foram revelados vários modelos que não deixaram ninguém indiferente e, com 2026 a aproximar-se, aproveitamos para assinalar os que mais se destacaram, seja pela sua “inteligência” e capacidades, por serem adoráveis ou por terem um aspecto arrepiante. A China tem vindo a apostar significativamente no desenvolvimento de robots humanoides e a Unitree é uma das tecnológicas que tem ganho destaque com modelos cujas acrobacias não deixam ninguém indiferente. O modelo G1 “roubou” as atenções durante o Web Summit 2025 em Lisboa, mas, este ano, a fabricante revelou uma nova versão ainda mais ágil. O robot R1 é capaz de correr, dançar. fazer o pino e ainda dar uns quantos golpes de kung-fu com as mãos e com as pernas. Segundo a empresa, o robot consegue responder a comandos de voz e até manter uma conversa graças a um sistema de IA multimodal que, além de reconhecer vozes, processa elementos visuais captados pelas câmaras. Com um preço de 5.900 dólares, o R1 é mais barato do que o G1, cujo preço ronda os 16 mil dólares, e é um modelo criado para developers, investigadores e instituições de ensino, mas também entusiastas de tecnologia com carteiras recheadas. Reproduzir o sentido de tacto tem sido um dos grandes desafios no campo da robótica, mas este é um dos obstáculos ultrapassados pelo Vulcan. O robot, desenvolvido pela Amazon, consegue sentir o mundo à sua volta, usando o tacto para percorrer prateleiras, identificar produtos e escolher os artigos certos nos centros de distribuição da gigante do e-commerce. Graças a uma ferramenta especial na ponta do seu braço, acompanhada por um conjunto de sensores que dizem quanta pressão está a exercer, o Vulcan é capaz de retirar ou arrumar objetos dos compartimentos sem danificá-los. No futuro, a Amazon tenciona implementar o robot em centros de distribuição nos Estados Unidos e na Europa. Ainda este ano, a empresa criou também uma nova equipa cuja missão passa por desenvolver agentes de IA para operações robóticas, com o objetivo de criar sistemas que permitam aos robots ouvir, compreender e realizar ações com base em interações de linguagem natural. Para o robot humanoide da Tesla, o ano foi de altos e baixos. Por um lado, a empresa de Elon Musk continuou a demonstrar as habilidades da mais recente versão, seja na pista de dança, com “moves” prontos para arrasar; a ajudar nas arrumações, ou até na passadeira vermelha para a estreia do filme Tron Ares, onde foi convidado de honra graças a uma parceria com a Disney. Por outro, incidentes como uma recente queda do Optimus num evento levantou novas dúvidas sobre o seu nível de autonomia. Num vídeo partilhado nas redes sociais é possível ver o robot a cair e a reagir de uma maneira estranha, levando muitos a acreditar que o modelo estava a ser controlado remotamente. Apesar disso, a empresa quer lançar a terceira geração do Optimus no primeiro trimestre do próximo ano, num modelo que, segundo Elon Musk, será tão avançado que vai parecer “uma pessoa a vestir um fato de robot”. Mas a Tesla não é a única fabricante de carros elétricos a apostar nos robots humanoides. Em novembro, a Xpeng revelou a mais recente versão do robot humanoide IRON, numa demonstração que deu que falar e que levou muitos a questionar se realmente se tratava de uma máquina ou de uma pessoa disfarçada. A empresa decidiu pôr tudo em pratos limpos para provar que o IRON não era humano e cortou a “pele” do robot para revelar os seus componentes internos.Momentos depois, o robot, que segundo a empresa se manteve ligado durante todo o processo, voltou a “desfilar” pelo palco, desta vez com o interior da perna exposto. A Xpeng afirma que a nova geração do robot tem movimentos mais realistas e fluidos, estando equipada com uma coluna e músculos artificiais, além de uma pele sintética flexível. O seu “cérebro” conta com chips de IA desenvolvidos pela empresa, bem como um sistema de IA criado especialmente para robots. A fabricante quer dar início à produção em massa de robots IRON já no próximo ano, com foco em aplicações comerciais e industriais. Os robots humanoides domésticos prometem ser uma das grandes tendências para os próximos anos e esta é uma área onde a 1X Technologies se quer destacar com o NEO. Ainda no início do ano, a empresa tinha apresentado o NEO Gamma, um modelo que funciona como uma mistura entre mordomo e empregado de limpeza, mas que também tem jeito para fazer unboxing de smartphones como se fosse um "influencer". Para a 1X o objetivo é que os seus robots consigam executar todas as tarefas domésticas que as pessoas fazem no quotidiano, como arrumar loiça na máquina de lavar ou dobrar roupa. Apesar disso, nesta fase ainda existem limitações, com algumas das funções a exigirem o controlo por parte de um humano. A mais recente versão do NEO já está a ser comercializada por 20 mil dolares. A empresa também disponibiliza uma opção que permite "adotar" um NEO através de um serviço de subscrição, igualmente longe de ser barato, por 499 dólares por mês. Se algumas empresas optam por dar um aspecto mais amigável aos seus robots domésticos, como o modelo apresentado pela Sunday Robotics, outras têm criações com “humanos sintéticos” cujo aspecto está entre o fascinante e o arrepiante, como o robot da Clone Robotics. A startup tem a ambição de criar robots “iguais” a humanos e o seu Clone Alpha está equipado com uma arquitetura com sistema de órgãos sintéticos para funções esqueléticas, musculares, vasculares e nervosas. De acordo com a Clone Robotics, o robot tem um esqueleto de polímero que imita a estrutura óssea humana, com 206 “imitações” de ossos ligados através de juntas articuladas com ligamentos artificiais. No futuro, o modelo será capaz de, por exemplo, memorizar o layout da casa limpa ou o inventário da cozinha; preparar comida, pôr a mesa e lavar a loiça; ou até manter uma conversa com convidados, afirma a startup. Depois de o demonstrar na CES no início do ano, a TCL levou o AI ME para a IFA 2025, onde “roubou” as atenções e os corações dos visitantes graças ao seu aspecto adorável e formato ternurento. Este robot modular foi desenhado para funcionar como um pequeno companheiro inteligente para os mais novos. Com olhos expressivos e uma voz que soa quase como uma criança, o AI Me é capaz de conversar, brincar e até ler histórias quando chega a hora de dormir. O robot, que ainda é um modelo conceptual, está equipado com câmaras e sensores que permitem captar fotografias e vídeos, reconhecer utilizadores e descrever o mundo que o rodeia. Este ano, a Nvidia, a Disney Research e a Google DeepMind juntaram-se para criar um novo motor de física para simulações robóticas. A Disney será uma das primeiras a usar o Newton para acelerar o desenvolvimento de robots para entretenimento, como os BDX Droids. O Blue é um destes robots e foi originalmente apresentado pela Disney Research em 2023. Com um aspecto que remete para a saga Star Wars, e até algumas parecenças com o protagonista robótico de WALL-E, o pequeno autómato ganhou mais vida com o novo motor de física. O Newton, que conta também com capacidades de personalização para experiências robóticas mais interativas, permitirá o desenvolvimento de robots mais expressivos, com capacidade de aprender a dominar tarefas complexas com maior precisão, afirma a Nvidia. Ainda no mundo dos robots com aspecto mais amigável, o Reachy Mini foi desenvolvido pela plataforma de IA Hugging Face para aumentar a utilização das ferramentas de desenvolvimento. O objetivo deste modelo, que se destaca pelo formato compacto, é que possa estar numa secretária ou na bancada da cozinha, sendo programado para a comunicação com os utilizadores de forma mais interativa. Com o Reachy Mini é possível aceder a milhares de modelos de IA pré-desenvolvidos, assim como criar novas aplicações usando Python. O robot está disponível em duas versões, uma standard, que chegará apenas no próximo ano, e outra lite, com um preço de 266 euros. Notificações bloqueadas pelo browser

Images (1):

|

|||||

| AI mapping system builds 3D maps in seconds for rescue … | https://interestingengineering.com/inno… | 1 | Jan 29, 2026 00:03 | active | |

AI mapping system builds 3D maps in seconds for rescue robotsURL: https://interestingengineering.com/innovation/ai-mapping-system-for-rescue-robots-mit Description: MIT’s new AI mapping system lets robots build accurate 3D maps in seconds, improving disaster rescue, VR, and industrial automation. Content:

From daily news and career tips to monthly insights on AI, sustainability, software, and more—pick what matters and get it in your inbox. Access expert insights, exclusive content, and a deeper dive into engineering and innovation. Engineering-inspired textiles, mugs, hats, and thoughtful gifts We connect top engineering talent with the world's most innovative companies. We empower professionals with advanced engineering and tech education to grow careers. We recognize outstanding achievements in engineering, innovation, and technology. All Rights Reserved, IE Media, Inc. Follow Us On Access expert insights, exclusive content, and a deeper dive into engineering and innovation. Engineering-inspired textiles, mugs, hats, and thoughtful gifts We connect top engineering talent with the world's most innovative companies We empower professionals with advanced engineering and tech education to grow careers. We recognize outstanding achievements in engineering, innovation, and technology. All Rights Reserved, IE Media, Inc. MIT’s new SLAM approach can process unlimited camera images and stitch submaps together to build 3D worlds in seconds. MIT researchers have built a new AI system that allows robots to create detailed 3D maps of complex environments within seconds. The technology could transform how search-and-rescue robots navigate collapsed mines or disaster sites, where speed and accuracy can make the difference between life and death. The system combines recent advances in machine learning with classical computer vision principles. It can process an unlimited number of images from a robot’s onboard cameras, generating accurate 3D reconstructions while estimating the robot’s position in real time. Robots rely on a technique called simultaneous localization and mapping, or SLAM, to recreate their surroundings and determine where they are. Traditional SLAM methods often fail in crowded or visually complex environments and require pre-calibrated cameras. Machine learning models simplified the process but could only process about 60 images at once, making them unsuitable for real-world missions where a robot must analyze thousands of frames quickly. MIT graduate student Dominic Maggio, postdoctoral researcher Hyungtae Lim, and aerospace professor Luca Carlone set out to fix that. Their new approach breaks a scene into smaller “submaps” that are created and aligned incrementally. The system then stitches these submaps together into one coherent 3D model, allowing a robot to move quickly while maintaining spatial accuracy. “This seemed like a very simple solution, but when I first tried it, I was surprised that it didn’t work that well,” Maggio says. As Maggio explored older computer vision research, he discovered why. Machine-learning models often introduce subtle distortions in submaps, making them difficult to align correctly using standard rotation and translation techniques. Carlone and his team addressed the problem by borrowing techniques from traditional geometry. They developed a mathematical framework that captures and corrects deformations in each submap so the system can align them consistently. “We need to make sure all the submaps are deformed in a consistent way so we can align them well with each other,” Carlone explains. Once Maggio merged the strengths of machine learning and classical optimization, the results were immediate. “Once Dominic had the intuition to bridge these two worlds — learning-based approaches and traditional optimization methods — the implementation was fairly straightforward,” Carlone says. “Coming up with something this effective and simple has potential for a lot of applications.” The MIT system proved faster and more accurate than existing mapping techniques. It required no special camera calibration or additional processing tools. In one demonstration, the researchers captured a short cell phone video of the MIT Chapel and reconstructed a precise 3D model of the interior in seconds. The reconstructed scenes had an average error of less than five centimeters. The team believes this simplicity could help deploy the method in real-world robots, wearable AR or VR systems, and even warehouse automation. “Knowing about traditional geometry pays off. If you understand deeply what is going on in the model, you can get much better results and make things much more scalable,” Carlone says. The research will be presented at the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) and is available on arXiv. Aamir is a seasoned tech journalist with experience at Exhibit Magazine, Republic World, and PR Newswire. With a deep love for all things tech and science, he has spent years decoding the latest innovations and exploring how they shape industries, lifestyles, and the future of humanity. Premium Follow

Images (1):

|

|||||

| Deep reinforcement learning for robotic bipedal locomotion: a brief survey … | https://link.springer.com/article/10.10… | 10 | Jan 28, 2026 16:00 | active | |

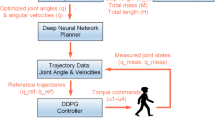

Deep reinforcement learning for robotic bipedal locomotion: a brief survey | Artificial Intelligence Review | Springer Nature LinkDescription: Bipedal robots are gaining global recognition due to their potential applications and the rapid advancements in artificial intelligence, particularly throu Content: